A Close Reading of Carl Phillips' Poem "Back Soon; Driving—"

What one might find along the scenic route.

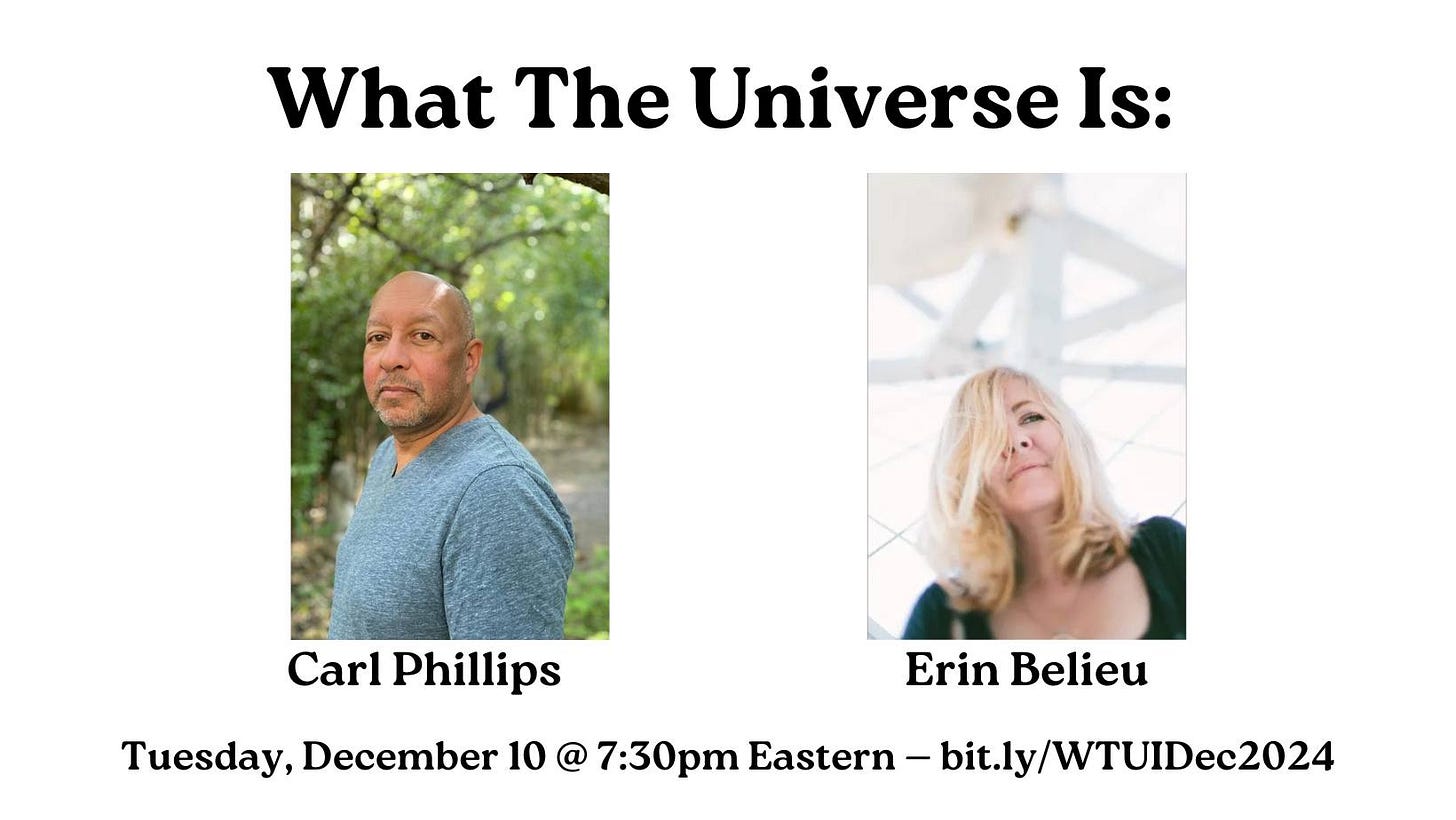

As 2024 judders and wheezes to a close, I’m excited to see this year pass into the rear view, but before it slips away fully, I’m also excited to host Carl Phillips and Erin Belieu for What The Universe Is: A (Virtual) Reading Series. One of the true high points of the past twelve months for me was having the opportunity to meet Carl and spend time with him when he headlined the Tell It Slant Poetry Festival with Sebastian Merrill back in September.

If you pay attention to the world of poetry (and I’m assuming that, if you’re here reading this Substack, you must pay at least a tiny bit of attention), you likely know that Carl won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 2023 for Then the War: And Selected Poems 2007 - 2020. It’s a richly deserved accolade, too; Carl’s poems are inventive and surprising and deeply humane in their consideration of what it means to live.

I hope you’ll make time on Tuesday, December 11 at 7:30pm Eastern to hear Carl read with his grad-school friend and fellow poet extraordinaire Erin Belieu. Register at bit.ly/WTUIDec2024 so you don’t miss out.

Back Soon; Driving— The way the present cuts into history, or how the future can look at first like the past sweeping through, there are blizzards, and there are blizzards. Some contain us; some we carry within us until they die, when we do. The snow falls there, barely snowing, into a long wooden trough where the cattle feed on those apples we used to call medieval, or I did, for their smallish size, as if medieval meant the world in miniature but not so different otherwise from our own, just smaller, a bit sweeter, more prone therefore to rot quickly, which is maybe not the worst thing. Revelation is not disclosure. I love how the snow, taking itself now more seriously, makes the cattle look softer, for a moment, than their hard bodies are.

There’s a fascinating interplay between the title of this poem and the poem itself; the title functions almost like a Post-It note that someone would leave for their partner to explain their unexpected absence, like something from the days before texting. I say this because it doesn’t seem to me to be waiting for a response — the em-dash really gives me that sense, anyway.

The diction in this poem is remarkably direct, even though it is also discursive and moving through abstractions in the opening lines. I can hear the different intonations in “there / are blizzards, and there are blizzards.” — as casual a conversational moment as I can imagine, and one that comes just before a memento mori moment, reminding us that when we die, our memories do, too.

The poem then cuts away from that image to a more concrete one:

The snow falls there, barely snowing, into a long wooden trough where the cattle feed on those apples we used to call medieval, or I did,

Since we know from the title that the speaker of this poem is on the move, I’m not too worried about how they encountered this “long wooden trough” — I live out in the country, really, and such things are common enough in the cultural awareness that even the slickest of cityfolk or those who live too far south for regular snowfall can conjure up an understanding of this scene.

There’s an associative leap in there, though: “those apples we / used to call medieval, or I did,” leads us into the very personal imagery of the rest of that stanza:

for their smallish size, as if medieval meant the world in miniature but not so different otherwise from our own, just smaller, a bit sweeter, more prone therefore to rot quickly,

“Medieval,” of course, doesn’t mean “the world in miniature” in any literal sense; it’s directly related to the so-called “Middle Ages” — the thousand years or so between 500 AD and 1500 AD in Western Europe. I suppose in a sense that limited perspective could be seen as “the world in miniature,” though I don’t think that’s what Carl’s going for here; nor do I think it’s the colloquial “going medieval on your ass” that comes to us from Pulp Fiction. It carries for me instead a sense, a connotation, of being closer to the source — perhaps closer to a Platonic ideal — and thus less desirable in a world just debased enough to prefer things that don’t rot quickly.

Is that right? I’m not sure, but it doesn’t seem to be contraindicated by the following line: “which is maybe not the worst thing.” It’s not the worst thing to be aware of the possibility that things haven’t necessarily changed for the better (though change, of course, is inevitable, just like the snowfall into the open trough.)

In a poem that depicts the covering-up of things with snow, especially one that is discursive and wanders as one who is out driving with no stated destination might wander, it is startling to find the statement “Revelation is not disclosure.”

In a literal sense, the outline of something — a trough, a cow — that is revealed when covered by snow is not truly disclosure of what’s beneath that snow. But “revelation” also carries a decidedly religious connotation (e.g., The Book of Revelation), which lends a certain heft to this statement; what is revealed here may be personal, private, not public.

A weird aside, because the term “disclosure” has taken on a particular connotation for those of us who are interested in UFOs (also known as UAPs). There is a subset of this subculture that believes the U.S. government (and other world governments) are concealing the truth about UFOs from the citizens of the world, and there are many, many theories out there about “soft disclosure” (the slow roll-out of extraterrestrial existence through pop culture) and conversations around the Congressional hearings that have happened in recent years acknowledging the military interactions with and documentation of UAPs. I would be absolutely shocked if Carl had this in mind when he was writing the poem, but it’s an example of how readers bring themselves to poems…and how sometimes we might just bring too much.

Back to the poem from that weird digression, where we find the snow “takes itself more seriously,” which I take to mean it falls harder, and in a beautiful irony, soften the “hard bodies” of the cows. This poem, like so many poems I love, isn’t about definitive answers. It’s the movement, as Kevin Prufer might say, of a mind across the page, and in that movement we are made privy to this speaker’s interior life, to what they notice about the world, to the connections they make with it, and to the connections we then might make with them through their language.

It’s a powerful, meaningful thing, this connection. We all need more of it. Come find some when Carl read with Erin on Zoom: bit.ly/WTUIDec2024.