A Close Reading of Molly Akin's Poem "Mothering is a social construct, and I am motherless"

In which I refrain from referencing either the Pink Floyd song "Mother" or the Danzig song "Mother" because neither one is germane.

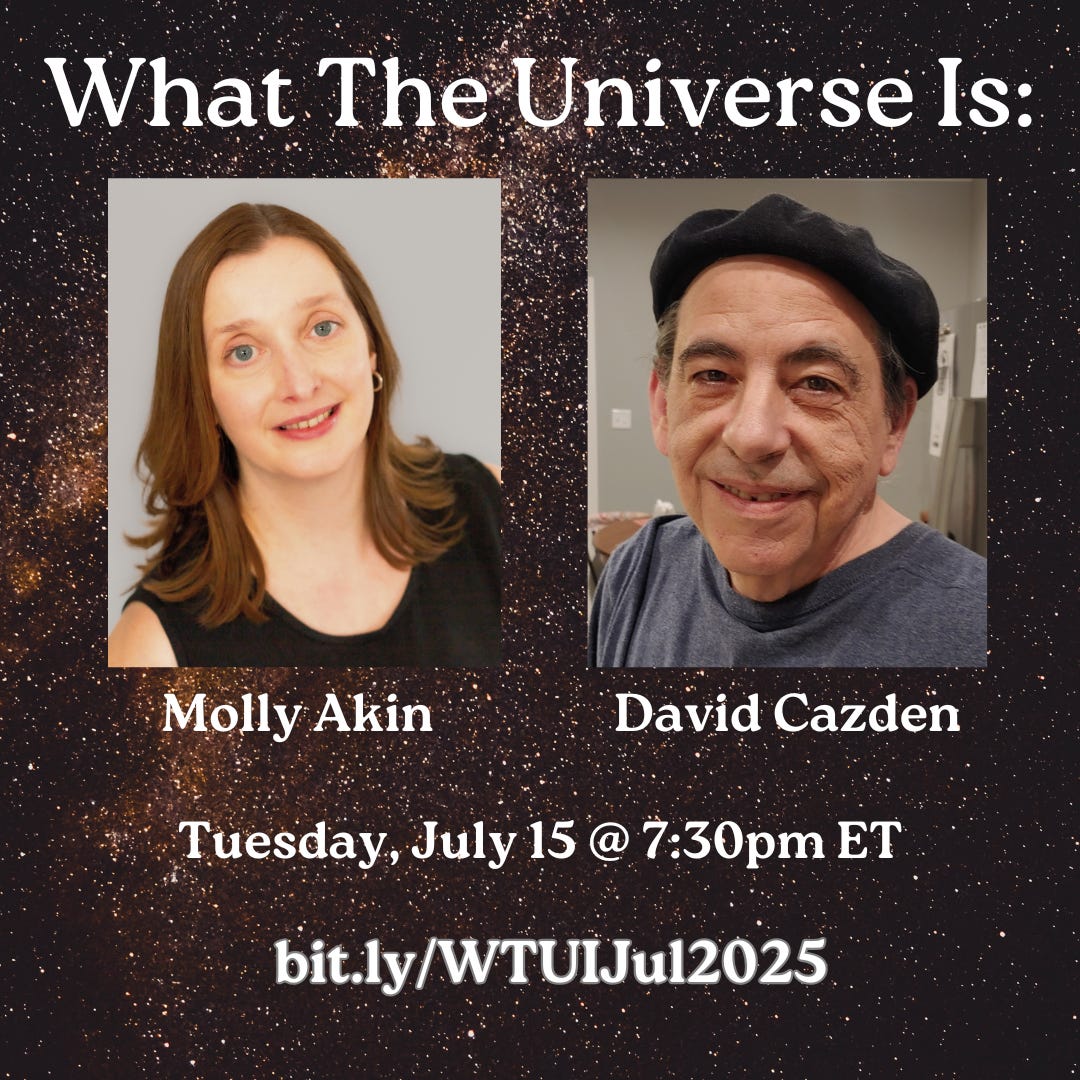

On Tuesday, July 15, at 7:30pm Eastern time, I will have the pleasure of hosting — and you will have the pleasure of hearing — Molly Akin and David Cazden. You must’ve registered by now, yes? bit.ly/WTUIJul2025 (just in case you haven’t.)

Molly and I first connected when she was part of the Emily Dickinson Museum’s Phosphorescence reading for the 2024 Tell It Slant Poetry Festival in September of last year. Molly read with two other WTUI alums, Jane Huffman and Diane Seuss, and I was fortunate enough to be in conversation with the three of them on behalf of the Museum. Molly read beautifully that night, as I know she will on Tuesday — I hope you’ll come through to hear both her and David!

Molly and I have since collaborated on a couple of other things, including a reading at this year’s Mass Poetry Festival that we called “The Informal Formal” — not content to just read poems, we built a panel that included Tatiana Johnson-Boria and Desiree Bailey, and we each read poems and then discussed the process of writing and revising them that shaped their final forms. I’ve really loved getting to know Molly’s work — and her poetic mind. She’s an exciting emerging poet, which you’ll see in the poem we’re looking at today. It first appeared in The Inflectionist Review, a journal that I would enjoy even if they hadn’t also published me.

Mothering is a social construct, and I am motherless There is no mother a fresh bell ring perhaps there was never “Mother” now absence is definite absence an old bell rung

If you’ve read any of my previous Substack posts — or if you’re one of the people who knows me “in real life” — there’s a good chance you’re aware that one of the great differentiating events1 in my early life was the death of my mother in 1993, when she was 53 years old and I was 18. So it should come as no surprise to anyone that I’d want to spend time with this particular poem of Molly’s.

The title is immediately and (I think) intentionally provocative; we do, after all, live in a time where “Gender is a social construct” has been used as both justification and instigation in online battles around gender identity2, but it’s even more provocative to follow “Mother is a social construct” with the second half of the title being “and I am motherless” — it’s the equivalent of a record scratch moment, which is not something one usually gets to see in a title.

As opening lines go, “There is / no mother” is about the only thing that could’ve followed that title; it calls into question the validity of the social construct of the title and gets me to wonder, at least, whether the mother in question is the archetype of mother, or whether it’s the speaker’s mother — and, truly, is there an archetype of mother, or do we all just imagine or recall our own mother? I was having tea with some friends this afternoon and, as part of our conversation, I mentioned that I truly don’t recall what my mother’s voice sounded like. She’s been gone for 32 years, and I don’t have any media with her voice on it (and if I did, it would likely be in a format I couldn’t easily access.) My memories of my own mother are at this point so subjective that I doubt they align with anyone else’s memories of my mother. Is this what it means that “There is / no mother”? The idea of the archetype of “mother” is profoundly unsatisfying to me, living as I do with only selected memories of my own mother.

And I recognize that other complication of archetypes — the unavoidable reality that not all mothers will meet the archetypal definition. Some mothers are neglectful, abusive, terrible in multiple ways. They’re as complex as their children, and reducing them to the archetype is unfair and inaccurate.

But we’re all brought into this world through the creative intervention of a mother of some sort. And “mother” can also be a verb, a metaphorical extension of the role in which new life is created, gestated, brought into this world, and (at least in some species) given care until the offspring is fledged or reared or weaned.

a fresh bell ring perhaps there was never “Mother”

There are so many ways to read these stanzaic fragments — is the “fresh bell” an emblem of realization that the concept of mother may never have existed outside of the Platonic ideal? Is this a statement on the relationship between the speaker and the person they called (rather formally) “Mother”? Is the mother in question undergoing a change due to dementia or Alzheimer’s, thus becoming less accessible to the speaker as a mother? Or is the speaker themselves a mother who, through loss of self or loss of other, has become unmothered or is now unmothering of someone else?

The openness of both form and fragment allow multiple readings that all center on the central question of the maternal relationship.

now absence is definite absence an old bell rung

The word “now” being on its own line puts a tremendous amount of pressure, of stress, on that word — this is no accident; that linebreak isn’t just an act of whimsy, but an announcement that there has been a breathturn3 in the poem, that we are moving into something like the denouement, though I can’t say that as we encounter an “absence” that “is definite” that we are finding full closure. Though we may be, as the speaker tells us that “an old / bell rung” — no punctuation, no finality at the end of the poem, and a tremendous caesura between “an” and “old,” which is a striking part of that line; there’s far more space than text, a gnawing sense of emptiness and only the most tenuous of connections there between those words. It feels like grief. It feels like realization. It feels a little bit like letting go.

Despite what pop psychology told us throughout the ‘90s, there’s really no such thing as “closure” when a foundational and fundamental relationship shifts — whether or not that shifting is an ending. If we are grieving something, we go on grieving it for the rest of our lives. We get better at carrying the grief, to be sure, but it’s not the same as being without the grief.

That’s the sort of complexity I think is at stake in this poem; the revelation that is contained in all of the open space, in all of the associative leaping between fragments.

It is both a vessel and a sieve for our own experiences. In this way, it is an act of immense generosity on behalf of the poet.

I hope you’ll come hear what else Molly will bring to What The Universe Is: A (Virtual) Reading Series with David Cazden on Tuesday, July 15, at 7:30pm Eastern. bit.ly/WTUIJul2025 will get you registered.

I’m honestly not keen on calling this a traumatic event, in part because the use of “trauma” as a qualitative marker in my own life events doesn’t feel helpful to me in terms of making meaning from them, and that’s what’s important to me. My mother’s long illness and early death shaped the trajectory of my life and my understanding of the nature and purpose of my own time on this planet — I suppose some people might see my deep investment in interpersonal relationships as a “trauma response,” but I might see those people as marginalizing or demeaning a decision I made after consideration of the fragile and ephemeral nature of our existence, an existence that only ever truly gets the meaning we’re able to give it. So, yeah, “differentiating event” because it differentiated me from other people in my life. My family members each dealt with it differently. We all still are.

I’ve always found this to be a sort of funny thing, as everything is a social construct. Lunchtime. Sports rivalries. Chauvinism about which city has the best pizza / hot dog / sandwich, etc. We’re a social species, and we construct this ongoing story we tell ourselves about our culture collectively.

In non-sonnet poems, I do tend to prefer Paul Celan’s neologism “breathturn” (atemwende in the original German) rather than volta to signal the turning point in the poem, especially as some poems have multiple turns. I also like the direct linkage to breath, to the reminder that poems live on the page and also in our physical bodies. Sometimes (as in this poem), the breathturn marks where the exhalation begins.

Michael, thank you. This poem in its short form says [to me], well, not says, but asks questions about the validity of motherhood. In a society run by labels, I wonder if motherhood is a label and not tangible. Are mothers needed, or are we only a vessel, then we die?